On Nov. 2, The Beatles, a band that broke up 53 years ago, released a new single. Billed as “the last song from the Beatles,” according to The New York Times, “Now and Then” is a fascinating case study for Beatles fans and those concerned with authorship and authenticity in music. This track has engaged listeners in a discourse surrounding modern musical ethics: When does a group author music, how should technology be used to manipulate and create music, and how does the release of “Now and Then” affect contemporary music?

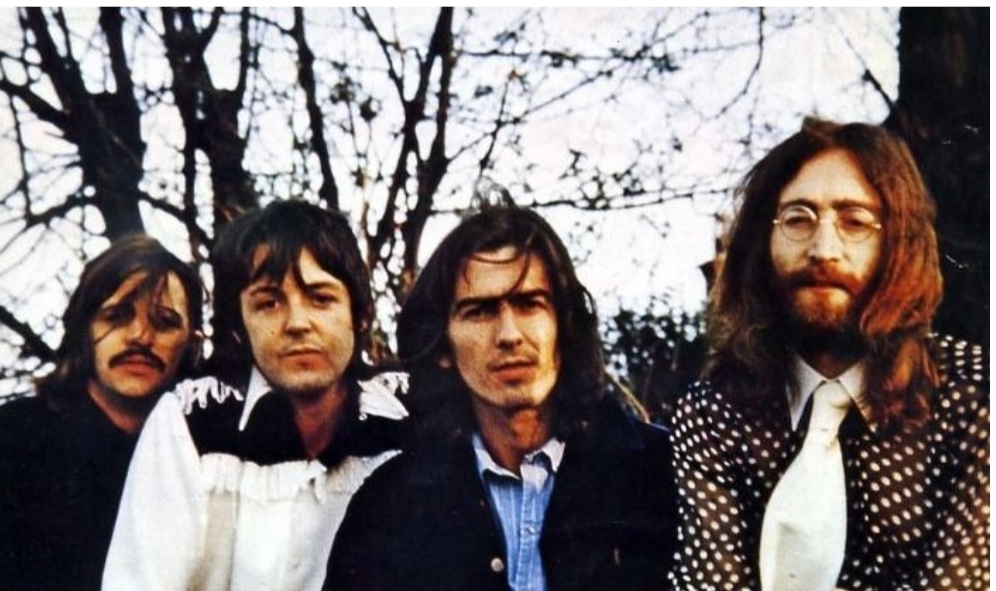

The history of “Now and Then” may be as intriguing as the music. The Beatles’ website states that in the late ’70s, several years after The Beatles disbanded, Beatles frontman John Lennon recorded a batch of solo songs at his piano in his New York City apartment using a low-fidelity handheld portable recorder. The songs were unissued at the time, and after Lennon’s tragic murder by a fan in 1980, his widow, Yoko Ono, gave these recordings to Beatles’ bassist Paul McCartney. In 1995, the surviving Beatles—McCartney, drummer Ringo Starr and guitarist George Harrison—produced a series of new Beatles “best of” albums called “Anthology.” As part of those records’ production, the three attempted to record new tracks on top of the 1977 Lennon demos. Embellished versions of Lennon’s “Free As a Bird” and “Real Love” were issued by the surviving Beatles as “new” singles from the band. However, the remaining Beatles passed on the demo of “Now and Then,” with Harrison, according to The Guardian, calling it “rubbish.” It is unclear whether Harrison did not like the song or if he felt it could not be issued because the audio was so poor. Harrison died in 2001 of cancer, never able to offer a definitive stance on the track.

In 2021, “Lord of the Rings” director Peter Jackson released the documentary “The Beatles: Get Back,” in which Jackson used artificial intelligence (AI) to isolate the vocals from instrumental parts in post-production on the featured songs. With the new technology, McCartney had the opportunity to return to “Now and Then,” and he gave Jackson the Lennon demos to see if they could be salvaged. With the participation of surviving Beatles McCartney and Starr, and using the guitar track Harrison recorded in 1995, “Now and Then” has now been issued as a new song. The final product was significantly reworked since its original iteration. “Now and Then” also includes new instrumentals, vocal harmonies by McCartney and Starr, and strings reminiscent of famous Beatles songs like “Here Comes the Sun” and “The Long and Winding Road.” A section sung by Lennon was also cut out. Perhaps the most significant controversy surrounding the track has been the revelation that McCartney used Jackson’s AI technology to separate out Lennon’s vocals and “clean up” the old recordings. The first insight into the song’s production that many Beatles fans gained came from an interview McCartney gave with the BBC, which suggested AI played a significant role in the new song by The Beatles. While that headline is hyperbolic, AI was, in fact, employed as an advanced form of mixing. The recent release of “Now and Then” raises many concerns surrounding musical authenticity, which AI “art” has catalyzed.

Is “Now and Then” a collective effort by The Beatles or a worked-over Lennon demo? Indeed, The Beatles’ discography often features contrasting musical ideas within the same song, seemingly a way of reconciling the band’s artistic differences. Take, for example, songs such as “A Day In The Life” and “Happiness is a Warm Gun,” which bisect into musically and tonally distinct hemispheres that reflect Lennon and McCartney’s competing creativities. It is thrilling to conceptualize “Now and Then” as a collaboration in that same style between The Beatles’ members spanning 46 years, through which McCartney and Starr have the chance to complete their deceased bandmates’ work. However, listeners cannot know whether Lennon or Harrison would have agreed to release this song had they been alive now, especially when Harrison objected to its release in 1995. Although “Now and Then” is undoubtedly a beautiful composition, propelled by Lennon’s mournful vocals, it is not especially revelatory about who The Beatles were or what they would have done if they had reassembled. It also does not help that the song sounds incomplete. Previous Lennon/McCartney collaborations have been intentionally disjunctive, with clearly delineated musical passages that call attention to their incongruity. Contrastingly, the luxuriant strings of “Now and Then” and Lennon’s iconic croon do not fully compensate for the ballad’s undynamic structure. These objections could have been curtailed if “Now and Then” had been billed as a Lennon/McCartney curiosity. Nonetheless, the single’s release under The Beatles moniker promises to make much more money for the participants involved.

Ironically, John Lennon’s last words to Paul McCartney before his death were purportedly, “Think about me every now and then, old friend.” The repurposing of Lennon’s final statement into the refrain of “Now and Then” is a melancholy torch-bearing moment—nonetheless, the cultural trauma of Lennon’s murder has long since faded. “Now and Then” represents the current iteration of an ongoing trend where the eminence of new artists is overshadowed by a returning act peddling out palliative, uncontroversial repetitions of older sounds. While contemporary and classic acts often “pass the throne,” as seen in McCartney’s collaborations with Kanye West, and Elton John’s work with Dua Lipa, the displacement of new talent by legacy musicians often enforces a musical gerontocracy in an industry where young musicians already struggle. “Now and Then” may feature a nice John Lennon vocal, but it is also a harbinger of a trend that threatens pop music’s increasing inclusivity and originality.