Everything in the universe can be traced back to a single point and the big bang that ensued. Similarly, if we delineate punk back far enough, we arrive at the prehistoric tribesman who decided to pluck a tensile string. After that, we encounter inaccuracy and conflicting opinions. Many rock artists of the 1960s and early ‘70s claim to be the one holy source of punk, but can there really be one?

By many definitions, the first official punk song was Ramones’ ‘Blitzkrieg Bop’. The song carried with it the three-chord simplicity, lack of refinement and macabre thematic outlook that would imminently define the genre. Additionally, the band’s long hair, ripped jeans, and leather jackets established the movement’s uniform in the run-up to Sex Pistols’ similar takeover in the UK.

Indeed, punk seemed to take off properly in 1976, but wasn’t Iggy Pop, the Godfather of Punk, doing essentially the same in the late 1960s and early ‘70s? By my personal metrics, The Stooges were the first punk band, while groups like The Kinks, The Who, and The Velvet Underground lit the way as integral luminaries.

The source and stature of punk changes depending on whom you ask. Since Sex Pistols’ founding bassist Glen Matlock is a bonafide Beatlemaniac and Ramones derived their name from Paul McCartney, they might cite the Fab Four as pivotal players on the road to punk. The Beatles themselves wouldn’t likely deny their role in the evolution, but they had mixed feelings about the movement when it arose in the mid-70s.

McCartney once commented on punk in a tentatively positive manner while speaking to The Quietus. “I understood that it needed to happen. It was a great thing, and something like ‘Pretty Vacant’ as a record is really good,” he said. Of course, his musical outlook is more complex and colourful, but he could understand the youthful resonance. Similarly, Lennon once described punk, as defined by Sex Pistols in the UK, as “great,” but he took issue later with the idolisation of Sid Vicious.

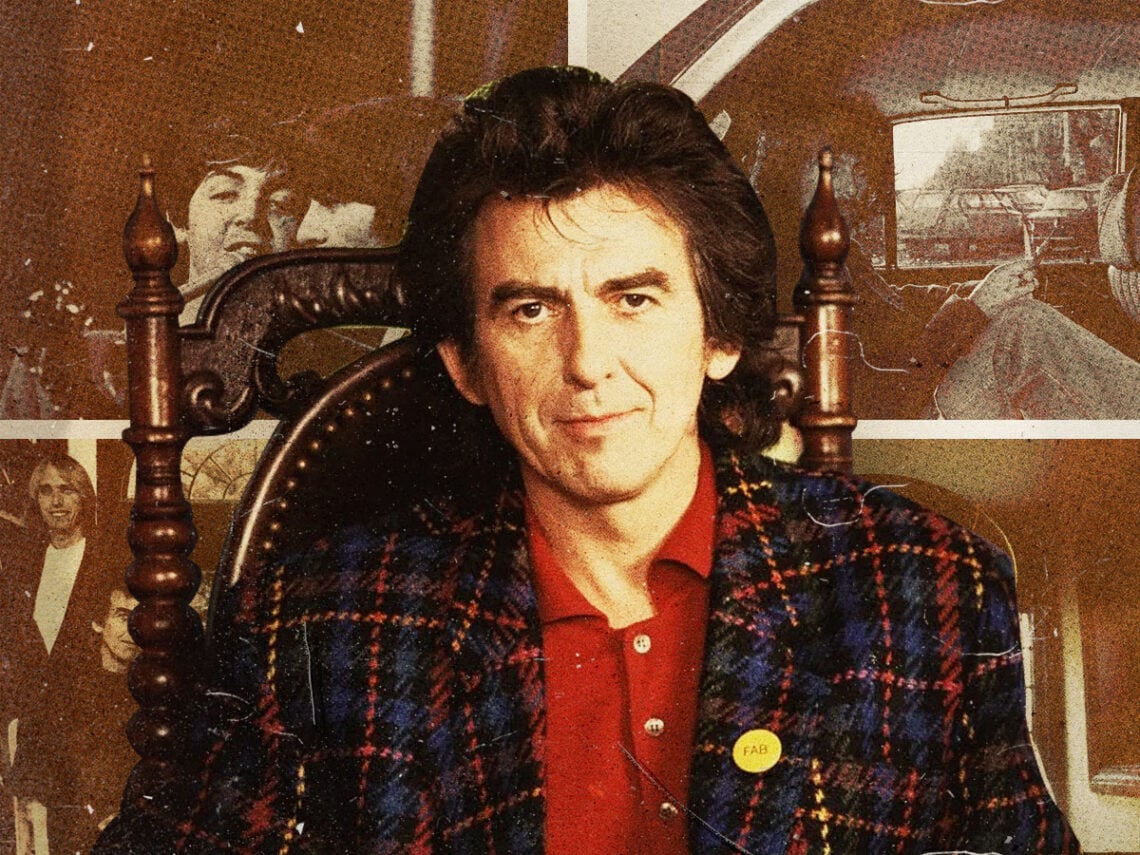

George Harrison, who was much less accepting of ego-driven music as a deeply spiritual individual, was less than impressed with punk. Discussing the movement in the US in the late 1970s, the former Beatle described punk as a transient trend. “I think even in England, it might have lasted a little bit longer than it did here, but it was a fad,” he said.

Although Harrison never fell victim to the punk spell, continuing with his colourful folk-rock after The Beatles’ split, he could understand why the movement came about. “That’s desperation that came out of,” he added. “You have to appreciate England to realise why the punk thing happened. I think those kids were brought up, not such good education, poor surroundings and trained to become working in factories, maybe bolting on hubcaps or something. It’s out of that, the desperation. Naturally, the thing is to destroy everything else around with the music.”

While Harrison could understand the appetite for destruction in the sociopolitical climate of 1970s UK, he seemed to suggest that it didn’t necessarily have a place in music. While pondering how music might evolve with British culture moving into the ‘80s, Harrison reflected on his own experience and outlined how, as purveyors of hope and joy, The Beatles stood in stark contrast to the punks. “I know in the ‘60s we and others worked hard to try and generate that positive feeling, and then in the end of the ‘60s, it sort of went a bit strange,” he explained. “Then the ‘70s just scattered around, and it was a bit ‘one fad after the other’ but nothing really long-lasting.”

As the respective members’ opinions demonstrate, The Beatles’ relationship with punk is rather complex. Undoubtedly, the band and their British Invasion rivals pushed the dominoes, resulting in the punk wave with its countercultural undercurrents. However, punk was less countercultural in the protest war in Vietnam vein and more of a generalised “don’t know what I want, but I know how to get it” call for revolution.