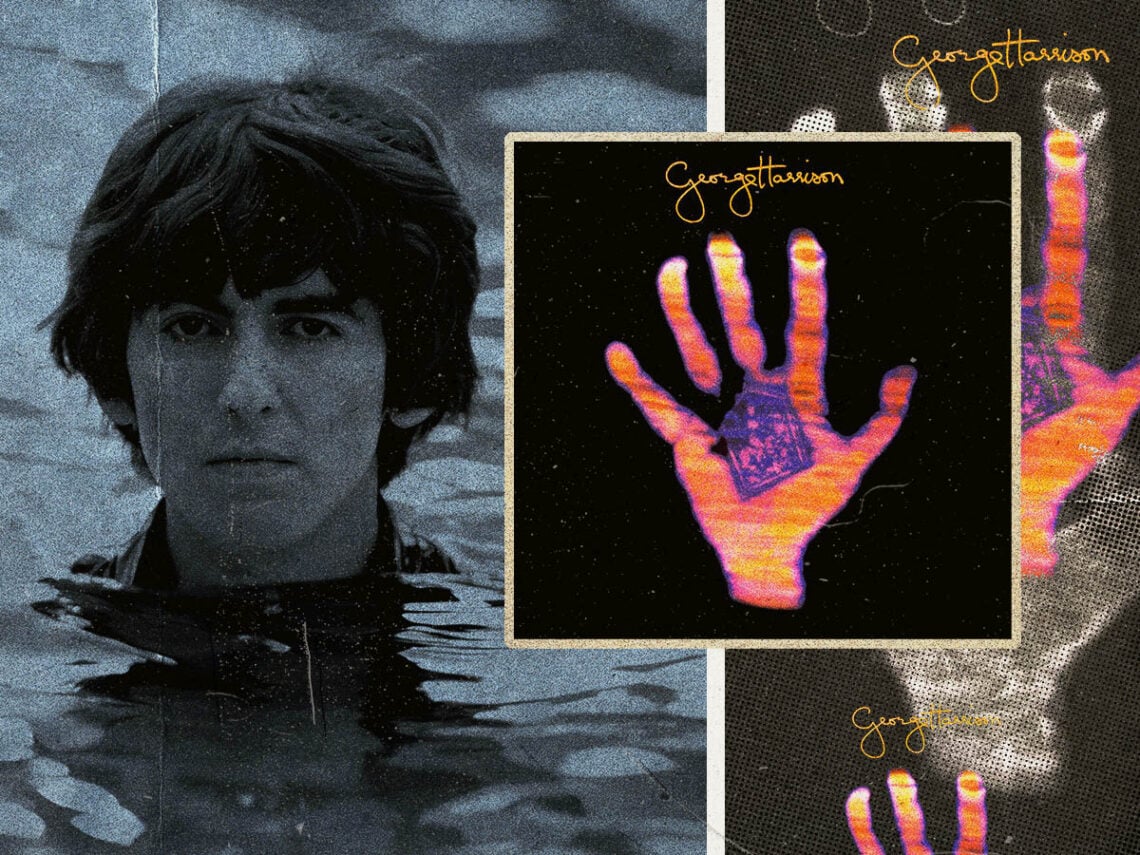

How do you come down from a high like The Beatles? It’s not an easy decision, but George Harrison needed to move on. Ever since the band’s breakup, the ‘Quiet Beatle’ had been riding the wave of his first solo album, which turned him into the most successful ex-Beatle on the strength of songs like ‘What Is Life’ and ‘My Sweet Lord’. If his guide to musical spirituality worked the first time, then Living in the Material World was about delving further into his psyche.

Opening on a ballad much like his previous effort, ‘Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth)’ is a gentle prayer for humanity, as Harrison muses about wanting something to help him cope with the heavy load on his back. The lyrics continue the conversations with God that he had on his first record, only much more direct, with a gentle acoustic guitar pushing the whole song along.

Throughout every track, the mission statement is about shedding all of one’s earthly hangups and getting in touch with the spiritual side of life. Nowhere is this more apparent than on tracks like ‘Be Here Now’, which offers a solemn prayer for everyone to slow down their daily lives and choose to live in the moment. Based on the Hindu meditation book of the same name, Harrison’s melody evokes the image of a glorious sunrise as he muses about the beauty that lives in the present and wants to capture that in song. Coming from the initial buzz of his solo career, there’s a chance that the magic of Harrison’s Hare Krishna mantras also found its way into this song…

Harrison isn’t alone in bringing these songs to the table, and it is to his credit that he didn’t let his ego get in the way of fruitful collaboration. Alongside him is German artist Klaus Voorman on the bass, who had previously worked on John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band and Rolling Stones collaborator Nicky Hopkins. While Harrison’s songs are already great if played on an acoustic guitar, the touch Hopkins has on the piano brings an aura of sophistication and even melodrama to some of the spiritual songs.

The drums provided by session drummer Jim Keltner also go down very smoothly. While he might not be the same as Ringo Starr’s trademark playing, his gentle pulse throughout the tune blends with Harrison’s inner sense of rhythm.

Then again, Harrison knows more than most about having to run away from his old band, and more than a few tracks on the record explore his preoccupation with the Fab Four. As much as the title track might be talking about the struggles of living in the material world, Harrison has sly bits of wordplay sprinkled throughout, like mentioning John Lennon and Paul McCartney by name in the verses and adding a subtle in-joke towards Starr towards the end.

When looking at the comedown from the ‘60s, Harrison’s ‘The Light That Has Lighted the World’ is one of his most open songs about his preoccupation with fame. Although some fans may have wanted The Beatles to go on forever, Harrison is crying out in this song about how hard it is for people to accept change. Just like all other survivors of the era, Harrison is content with Lennon saying, “The dream is over”, and is ready to pick up the pieces and move on to the next phase of his life.

Outside of his old band, Harrison deals with the other headaches that connect him to the material world on ‘Sue Me Sue You Blues’, a dirgy track which deals with the lawsuits that he was tangled up with after the plagiarism of The Chiffon’s ‘He’s So Fine’ for ‘My Sweet Lord’. Harrison might have had to fight like hell to hold onto his songs, but the fact that he put this into one of his tunes provides a bit of tongue-in-cheek humour to the whole track.

In addition to his devotion to faith, Harrison branches out into new sonic territories on this record. For the first time since The Beatles’ track ‘The Inner Light’, he uses Indian instrumentation across the album, with the sitar and tabla returning on the title track as well. When talking about Harrison’s playing, it all comes back to the slide guitar, including a handful of songs that Harrison uses to express emotions that can’t be spoken. While Eric Clapton may have been known to abuse his guitar, Harrison’s delicate touch with the slide is enough to make anyone weep, never mind the guitar itself.

Outside of the instrumentation, this album features some of the strongest singing of Harrison’s career. Having given up smoking for a time during the recording of this album, there are no hangups in his vocal style, only belting when he needs to and delivering every song with as much earnest emotion as possible.

There is also a deep soul influence on the song ‘Try Some Buy Some’, which Harrison would ultimately give to Ronnie Spector. While it might not be at the same level as Marvin Gaye or Smokey Robinson, Harrison has a good handle on the format.

The album comes to a breathtaking close on ‘That Is All’, lulling the listener back to where the album started with a ballad. Though Harrison’s vocals might not be the strongest on this track, it sounds like he’s crying out for salvation from the Lord or his fellow bandmates.

So after coming off one of the most significant Beatles solo records, Harrison matched it with an album that was just as emotionally potent without any of the bombasts. Though the linger production from Phil Spector might be hard to stomach at points, there isn’t an ounce of pop cynicism in any of the tracks on here.

Throughout the various headaches of his earthly constraints, Living in the Material World is a mature study of what makes Harrison tick and how he might be able to remain spiritually conscious in his vessel. He might have been The Beatle that changed the most, but Harrison was looking for something more than just writing pop music, and that earnest tone bleeds through every track.