In not much more than a decade, The Beatles managed to write around 230 songs, depending on who you ask. That’s roughly 21 a year. Considering that they now have 21 number-one singles to their name, you wouldn’t be far wrong if you said a tenth of their work was chart-topping. Needless to say, that’s an absolutely mind-boggling feat.

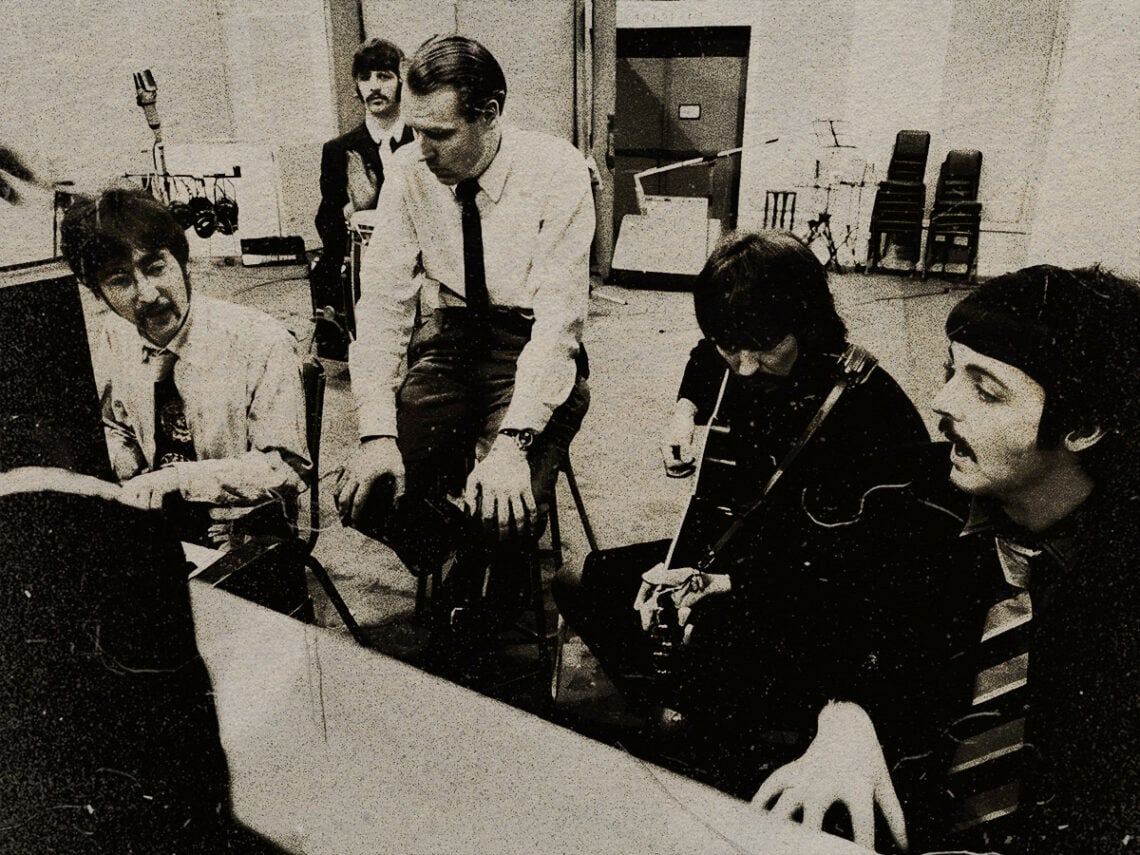

Considering that they were also fearlessly pushing boundaries while they were at it, adding orchestration to rock ‘n’ roll, getting experimental with new technology and avant-garde quirks, it’s even more miraculous. Naturally, such a heady full steam ahead pursuit left a few little errors in the works and ungrounded rumours that session musicians occasionally cleaned things up abound. But, in truth, it’s incredible that four young lads and George Martin didn’t happen upon more mistakes in this whirlwind.

Alas, there is one that stuck out to the late George Martin that he feared could not be unheard. It’s a marvel of music that it’s never the same twice: every song is a fluid piece of art, and every masterpiece you’ve ever heard might have sounded different on another day, another take, another millimetre of microphone placement, and so on. This very notion struck John Lennon when they were recording the masterful ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’.

Listening back, Lennon liked the opening section of one, but the finale of another. Given that there is quite a distinct divide in musicology and instrumentation, the bespectacled Beatle suggested that their deft producer splice the two tapes together. He undertook this difficult task with great skill, perhaps just a tad begrudgingly. The fact that this splicing was hitherto unknown to millions of fans and the song is deemed a masterpiece is evidence that he pulled it off.

But Martin opined: “There are two things against it. They are in different keys and different tempos. Apart from that, fine.” He ironed out these issues by marginally speeding up the first tape and ever so slightly slowing the second to create a seamless marriage while adding a flourish to mask where they meet.

Nevertheless, if you listen closely enough, you can just about hear the slight transition at the 60-second mark. While this has subsequently been ironed out further on recent remasterings, it hid in plain sight for years. The backstory also helped to spawn what is now a common practice in music, with splicing a simple digital process these days, growing easier by the day by the same AI that helped to bring us ‘Now and Then’—completing an apt circle and showcasing the band as eternal pioneers.

While people were busy listening out for “I buried Paul” (which is actually Lennon shouting “Cranberry sauce”), the evident mix at 59.05 was lost in the welter as just another supreme orchestral arrangement development by the band, which, in a way, it was.