As it turned out, on that day they didn’t finish the work in the morning and afternoon sessions. In fact they were still there at ten o’clock at night, the point in the evening when Abbey Road neighbours were inclined to complain, particularly if a band was using the echo chamber on the outside of the building. Most of what they had recorded that day would go on the first LP but George Martin decided that “Hold Me Tight” was not quite strong enough yet and therefore he needed another tune to complete the record. They took a break in the canteen in the basement to decide what it might be. It was Alan Smith, a journalist friend from Liverpool who was with them that day writing a story for NME, who suggested they do “Twist And Shout”—or, as he said at the time, “the thing you do that sounds like ‘La Bamba.’” This seemed as good an idea as any. They returned to Studio Two and took up their positions. They were exhausted by the demands of the day and thinking about how early they would have to get up in the morning. John was further wondering whether his flu-racked voice could possibly hold up for the performance ahead.

“Twist And Shout” had been recorded by American R&B groups the Top Notes and the Isley Brothers. Both recordings are in their different ways very American and twist-worthy in a decorous way. You could imagine advertising men dancing to it in New York’s Peppermint Lounge. In the hands of the Beatles in Studio Two that night in June 1962 the song was not so much transformed as transcended. If Norman Smith required any vindication of his quest for a new, live sound, “Twist And Shout” provided it. While the combined vocal and instrumental attack of the other three shut off any possibility of retreat, John Lennon sang the song like it was the last he would ever sing. Since they abandoned a further take, this was what “Twist And Shout” proved to be for that night and for every other night of their touring years. It became the closing track of the LP they were making that day. It became the closing song of every show they would do in that year of Beatlemania. It became the song that more than any other the Beatles always had to do. In the sense that the record’s less about the song than it is about the delirium of the delivery it is the record you could use to explain the Beatles to a Martian. And although it didn’t strike anyone at the time, it turned out that between them the Beatles, George Martin and Norman Smith had stumbled upon a sound which was about to give old American rock and roll a new birth of freedom in north-west London.

Thirty years later writers like Ian MacDonald were still trying to understand what they had managed to do at the end of this session. The intensity of “Twist And Shout” didn’t simply come from the performance. It also came from the manner of the recording. At the height of the beat mania of the winter of 1963 lots of young bands would be going into the studio for the first time to turn their live act into their first album. Most of the time that would result in little more than at worst a sobering reminder of their shortcomings and at best a useful audition tape. “Twist And Shout” by the Beatles was something more than that. It communicated how their music felt, which was a different thing entirely. It conveyed the excitement the Beatles could generate. It also seemed to communicate how excited they felt about that excitement. It conveyed them.

In the wake of the desire to install the Beatles securely in the pantheon of so-called serious artists has come a tendency to place too much emphasis on their songwriting and not enough emphasis on the way they performed songs, even when those songs were written by other people. “Twist And Shout” is the key example of this. By the time they had finished with it, it was their song. It was the perfect vehicle for them to put over their special sauce, which was what happened when they sank their individuality into the group. Once you had heard them do these American songs you no longer had much time for the so-called originals. This was no longer a group trying to sound like anyone else. This was a group who wanted to sound like themselves. That was what shone right through “Twist And Shout.” As Ian MacDonald was to say of the record in his book Revolution in the Head, “nothing of this intensity had ever been recorded in a British pop studio.”

It was also, along with the song that started the album, “I Saw Her Standing There,” the first of their records that could be called great in the sense that it would have stood against those coming out of Motown or Nashville at the time. Just five months later, on 1 July 1963, they were back in the same studio with a new song they had written and rehearsed in the previous four days. Norman Smith later remembered taking a look at the song’s words, which had been written out and left on a music stand. He was dismayed at their seeming banality, much as Paul McCartney’s amateur musician father had been when it was performed for him in their living room. Neither of them were wrong.

As a song, “She Loves You” was banal. Staggeringly so. But when you heard the people who had written it play it, that was no longer the case. When you heard them sing it, a whole new dimension opened up. You heard what they had been imagining when they were writing it. When you heard the way their performance sold this scrap of nothing there was no alternative but to surrender. And when you heard the recording back you realized that this group was not only more of a confederacy of equals than any group had been before, it was also capable of getting more of its mystery ingredient on to tape than any group had previously done. That was “She Loves You,” the record that brought a world to its knees. No short era of recording has been as pored over as the Beatles’ time at Abbey Road in the 1960s.

Everybody who had even the most glancing acquaintance with them and their deeds during this time has their anecdotes, small chapters in the greater creation myth with which they understandably do not wish to tamper. Memoirs have been written, often many decades after the events, which do not always square with other memoirs. In each case there is a tendency to place the author at the centre of the most momentous events, a tendency which is entirely understandable. In other cases entire episodes have been recalled which others who were there do not remember at all. Everyone has their anecdote, the culmination of which is the blob of solder they applied, the edit they made, the suggestion they put forward which played some part in nudging in this direction or that a piece of music with which we are all familiar, deep in our bones.

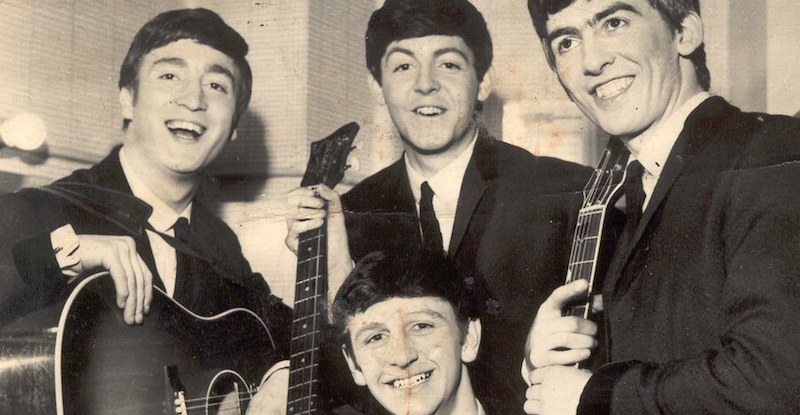

Geoff Emerick, the engineer who was to be to the second half of the Beatles’ recording career what Norman Smith was to the first, was in the studio that day helping out. In his memoirs, written in a different century, he describes how on this particular day the Beatles were doing a photo session outside the back of the building which resulted in a stampede of fans which in turn led to the building’s security being breached and hysterical girls tearing through the offices in search of a Beatle before being eventually evicted. He describes how the excitement of these events may have fed into that day’s recording, how “She Loves You” was the way it was because it was made with the hot breath of Beatlemania upon its cheek.