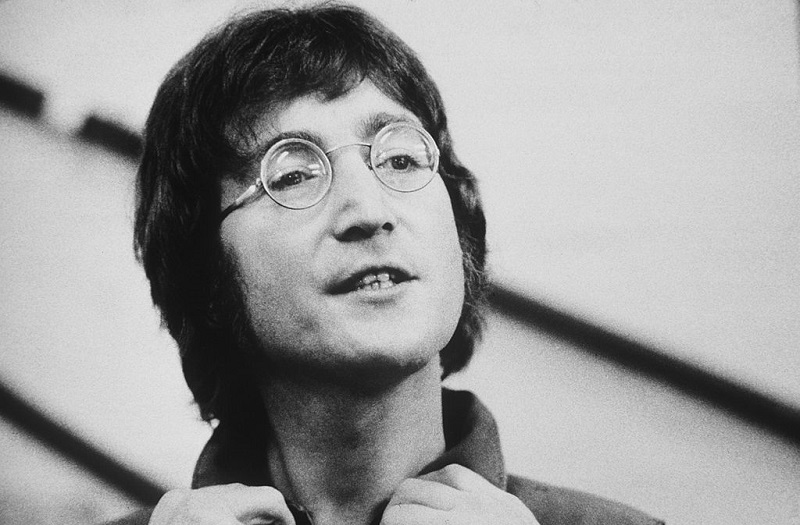

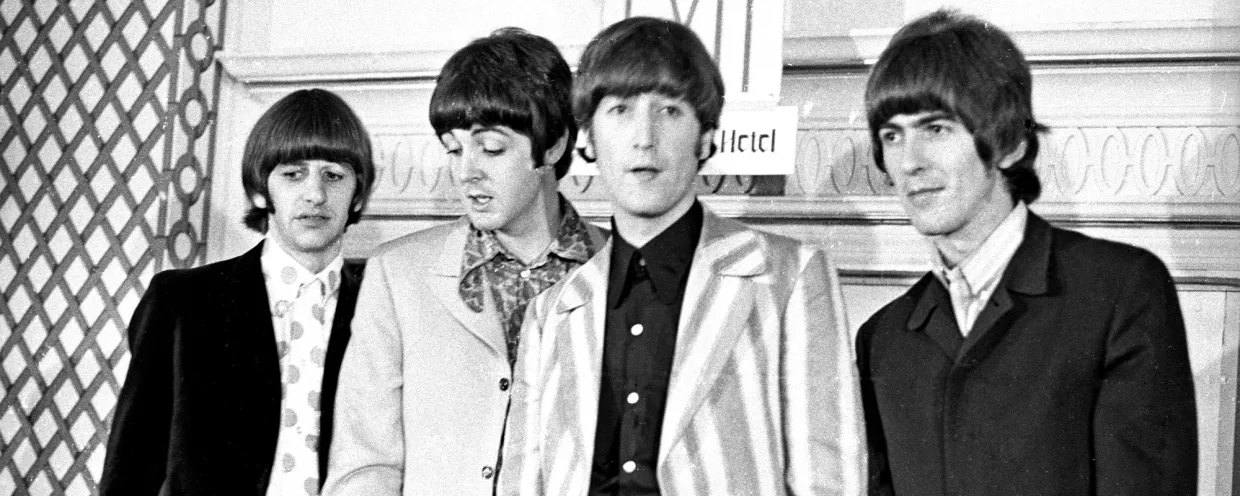

Being in the biggest band of all time came with a blueprint. Inevitably, to keep up with their widespread appeal, it wasn’t all artistry and celebrating the changing zeitgeist for the Fab Four. The group had to adhere to a schedule of releases that would make modern musicians baulk, often delivering two to three projects per year at their Beatlemania height. The business end of certain projects were far from ideal for the egos of The Beatles. One project, in particular, was described by John Lennon as a “fuckin’ humiliation”.

Part of The Beatles trailblazing journey in the realm of culture was tied to how they embraced elements of the music industry that stretch beyond LPs and touring. The 1960s wasn’t just about relinquishing the shackles of the Second World War, which had debilitated much of the world for a decade after a ceasefire was agreed, but also looking to the future. Making movies equally forgot about the past and, instead, wanted to focus on modern icons.

As such, The Beatles’ gilded music career was permeated by five movies – A Hard Day’s Night (1964), Help! (1965), Magical Mystery Tour (1967), Yellow Submarine (1968), and Let It Be (1970) – that celebrated irreverence and brought personality to their oeuvre. However, before mystic psychedelic-induced introspection entered into the cinematic process, the carefree fun sometimes seemed a little too frivolous for Lennon and the band.

In the novel Lennon Remembers, his feelings about filming Help! were made abundantly clear. During the filming process, young fans were whisked onto the set with their parents at various intervals and the Fab Four were forced to meet with them or risk the wrath of the press “turning on them”.

“It was the most humiliating experiences for me,” Lennon said. “Like sitting with the governor of the Bahamas because we were making Help! and being insulted by these fuckin’ jumped-up middle-class bitches and bastards who would be commenting on our work and our manners. And I was always drunk, like the typical-whatever it is-insulting them. I couldn’t take it. It hurt me so, I would go insane, swearing at them and whatever.”

“It was a fuckin’ humiliation,” Lennon remarked of the ordeal. “One has to completely humiliate oneself to be what The Beatles were, and that’s what I resent. I did it, but I didn’t know. I didn’t foresee that, it just happened bit by bit till this complete craziness is surrounding you.”

The movie was also filmed just after The Beatles famously shared a toke with Bob Dylan in New York’s Delmonico Hotel, so it was probable that Lennon was a touch more than merely drunk on set.

As John Lennon told David Sheff in the novel, All We Are Saying, “The Beatles had gone beyond comprehension. We were smoking marijuana for breakfast. We were well into marijuana, and nobody could communicate with us because we were just glazed eyes, giggling all the time.” The band could barely remember their lines for the Help! picture, and they spent most of their time on set gorging themselves on cheeseburgers.

Beyond intoxication, the moment is also seen as a pivotal one for the group artistically. It was after this connection with the folk hero that the band started to look inward when writing their songs, shying away from aiming their well-crafted number-one rifle directly at teenage life, love and unrelenting lows. They pulled away from making purely pop hits, and instead made music for themselves. It would see them create perhaps their finest work. Lennon’s reaction to the Help! movie is likely his feelings towards the band’s past in general.

Despite the perceived blemish on the band’s artistic integrity, both on set and the production in general, the movie’s reception proved once more that even when The Beatles missed, they scored. Help! was a triumphant success and even inspired the classic Monkees sitcom of the late sixties, in another example of how the group paved the way into the future that others followed them down.

Lennon’s disgruntlement with the public perception of The Beatles would continue into their later years. He was annoyed when fans didn’t understand the group’s willingness to move away from pop. As their lyrics became poetic and almost indecipherable, he made fun of The Beatles intellectuals who tried to study their work. As the notion of their “philosorock” grew, he wanted the band to turn back to being rock and rollers. It would seem he was rarely satisfied that anyone but Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr truly understood the band and their evolution as artists — and often, not even them.