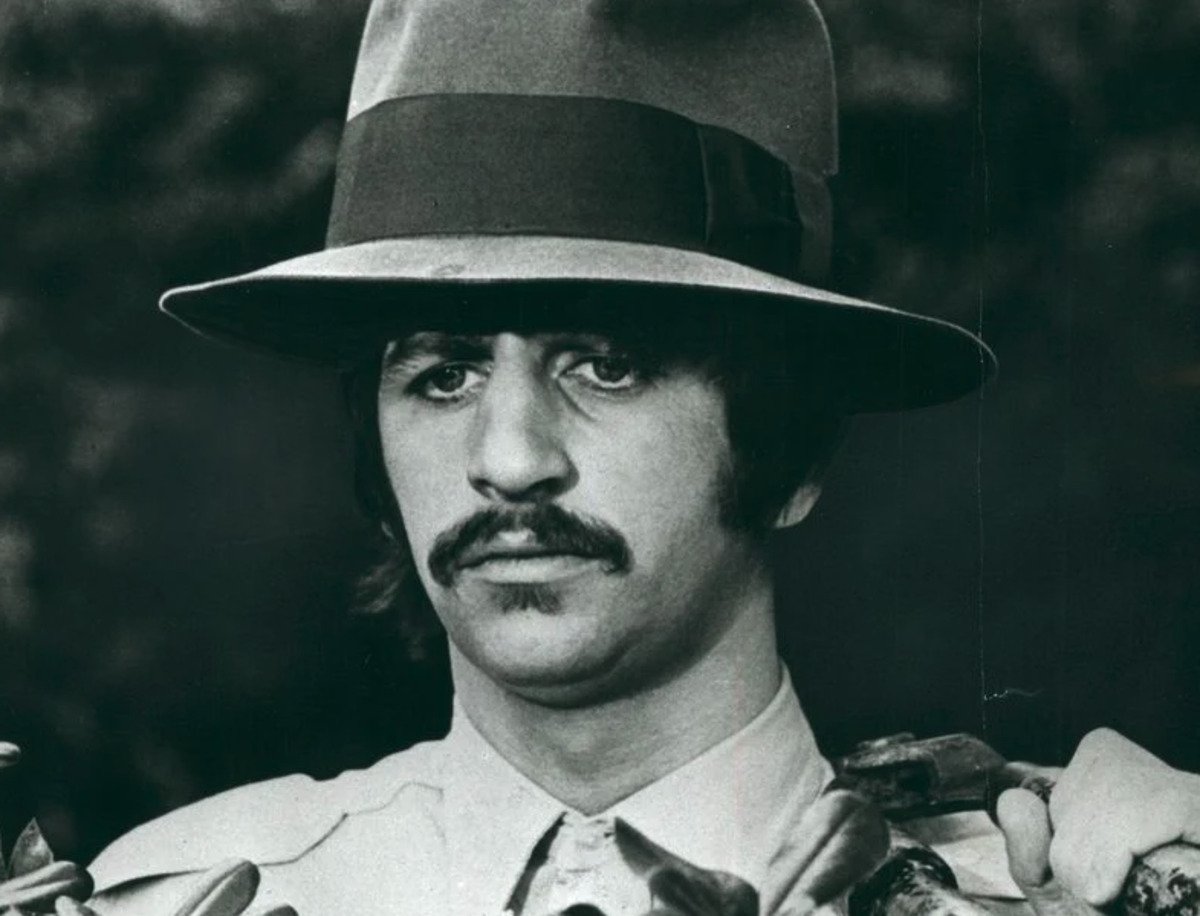

In the throes of Beatlemania, fervent fans of the Fab Four would never have known the band would disband in years to come. But behind closed doors, cracks were already starting to show. On August 22nd, 1968, drummer Ringo Starr walked out of the White Album recording sessions, almost six years to the day that he first performed a show with the band.

But it was only the staff at Abbey Road Studios who had any inkling of tensions at the time. Although it never made it to the press, engineers would be told to leave the room while heated discussions took place. Eventually, the atmosphere got the better of Starr, who was beginning to feel like an outsider in his own band. Abbey Road staff noted that Starr was often the first to show up at the studio, and would often sit in wait for the others – an increasingly uncomfortable dynamic for Starr.

As he later confessed in Anthology, Starr felt his playing was suffering at the time as a result, and he found it increasingly difficult to watch the other three quite content as he sat on the outskirts. “I went to see John [Lennon], who had been living in my apartment in Montagu Square with Yoko [Ono] since he moved out of Kenwood,” Starr wrote. “I said, ‘I’m leaving the group because I’m not playing well and I feel unloved and out of it, and you three are really close.’”

Lennon said, “I thought it was you three!” when Starr expressed he felt somewhat overlooked, and when Starr knocked on McCartney’s door, sure enough, the guitarist said: “I thought it was you three” too. It was a sign the band was getting thrown by their own tension, each feeling like the lesser in their own way. The stress of Beatlemania, Lennon’s drug use, and his relationship with Ono left a smouldering resentment bubbling under the surface for Starr.

Producer George Martin offered his own theory for Starr’s temporary exit, saying: “If you go to a party and the husband and wife have been having a row, there’s a tension – an atmosphere,” he said. “And you wonder whether you are making things worse by being there. I think that was the kind of situation we found with [Starr]. He might have said to himself, ‘Am I the cause?’”

Starr left for Sardinia, borrowing a yacht of Peter Sellers while he cleared his head. It was during this time Starr wrote ‘Octopus’s Garden’, which would later be released on 1969’s Abbey Road, marking Starr’s second-only solo composition for The Beatles. Starr had been chatting with idly the captain about the life of an octopus and brought his childlike fascination into the song.

“They hang out in their caves and they go around the seabed finding shiny stones and tin cans and bottles to put in front of their cave like a garden,” he said in Anthology. “I thought this was fabulous, because at the time I just wanted to be under the sea too. A couple of tokes later with the guitar and we had ‘Octopus’s Garden.’”

While Starr was ruminating on the habits of sea creatures, the other three Beatles were hard at work, with McCartney filling in for him on drums on ‘Back in the U.S.S.R.’ and ‘Dear Prudence’. Evidently, it only took recording two songs without Ringo for them to realise they needed him. The group sent the drummer a telegram saying they loved him and that he was the best rock and roll drummer in the world.

Starr returned to Abbey Road in September. His drum kit was covered in flowers in a message that read: “Welcome back, Ringo”.

After a rocky spell of insecurity within the band, there couldn’t have been a more fitting way to welcome him back into the fold. It was McCartney that would reflect on Starr’s position in the band and their role in his self-doubt. “I think [he] was always paranoid that he wasn’t a great drummer because he never used to solo,” he considered in Anthology.

“You go through life and never stop and tell your favourite drummer that he’s your favourite. Ringo felt insecure and he left, so we told him, ‘Look man, you are the best drummer in the world for us,’” he added. “I still think that.”