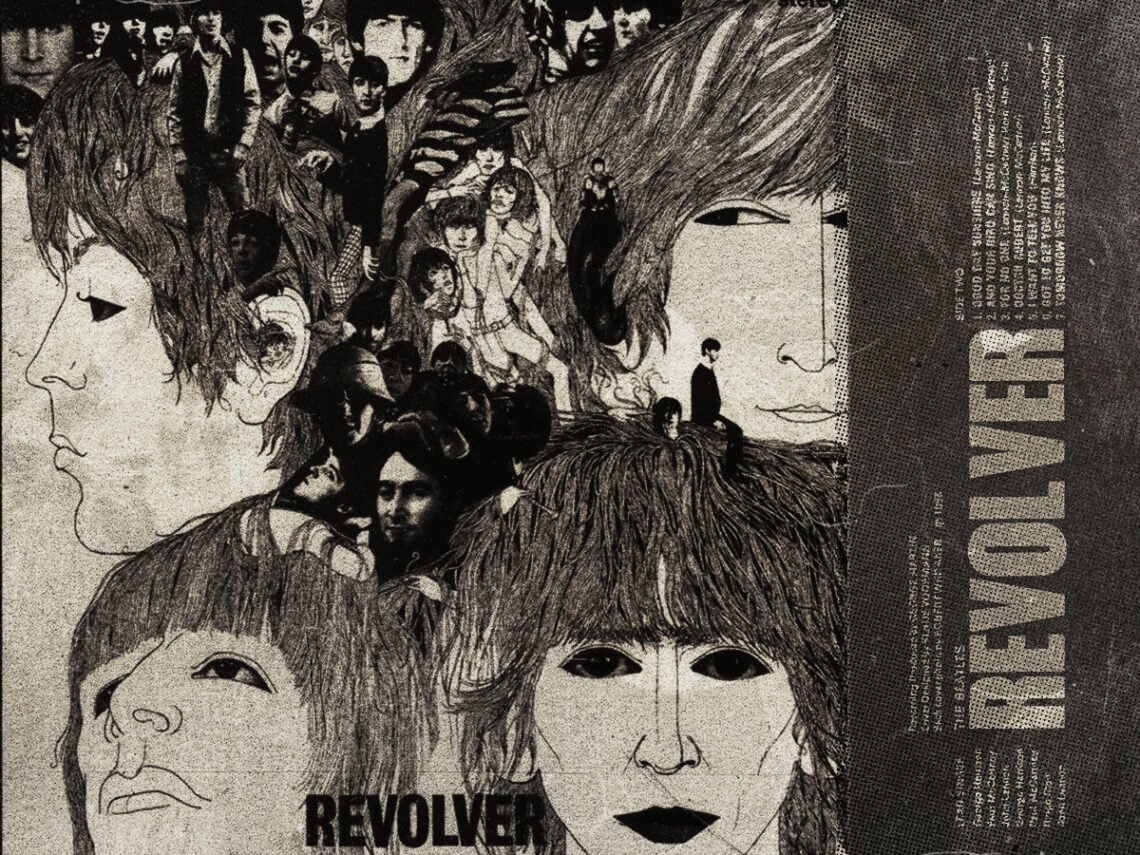

On June 23rd, 1966, The Beatles embarked on their last-ever global tour. They’d just finished recording their latest studio album, a kaleidoscopic progression through the future of rock and pop music, drawing on influences which ranged from The Byrds to Johann Sebastian Bach. The only thing it lacked was a title.

Before leaving, the group had told EMI, the parent company of their record label in the UK, that the album’s name would be ‘Abracadabra’. There was a problem, though. Another artist had already released an album by that name. At the time it was universally seen as bad practice to use the same title as a pre-existing work for your LP.

And so, the Fab Four set about brainstorming an alternative name while cooped up in German hotel rooms. John Lennon, who was then burying himself in psychedelic drugs and the writings of psychologist Timothy Leary, suggested the multi-dimensional paradoxes ‘Four Sides of the Circle’ and ‘Four Sides of the Eternal Triangle’.

Ringo Starr, who was thinking more literally, focused on the theme of touring, which the band were already preparing to give up. Parodying the recent Rolling Stones release Aftermath and the early Beach Boys record Surfin’ Safari, he came up with the ideas ‘After Geography’ and ‘Beatles on Safari’.

Whether intentionally or not, Paul McCartney synthesised the thought processes of both Lennon and Starr. Their markedly different suggestions all circled around the common themes of movement, change and transcendence, as well as the multi-faceted nature of the album and its track listing. Each song seemed in a different direction from the one before it. Like ‘Pendulums’, McCartney thought, which encapsulated both the avant-garde mystique of Lennon’s ideas and the sense of movement and travel in Starr’s.

So, how did they settle on their final choice?

Even this option wasn’t considered strong enough, however. It just didn’t stick in the mind. Neither did Lennon’s, as profound as they were conceptually. And the band felt Starr’s pastiche titles were too goofy to do justice to the work.

The brainstorming continued, staying with the theme of movement to reflect the extraordinary progression of the band’s sound on the album and their determination to leave Beatlemania behind them and move forward. This is a record about motion, a record in motion. How does a record move?

McCartney describes the eureka moment when the group finally found the word they were looking for in the mini-documentary about the making of the album released in 2010. “We suddenly thought, ‘Hey! What does a record do? It revolves. Great,’” he recalled. “And so, it was a ‘Revolver’.” The name was also a pun on the common word for a handgun with revolving bullet chambers, which was especially prevalent in the common lexicon of the era thanks to the popularity of John Wayne and Clint Eastwood westerns.

But it wasn’t only a play on words, as the previous album Rubber Soul had been. Or simply a representation of the band’s progress from its beginnings as a live-beat group. Or even of the movement between genres and sounds that takes place from song to song and, in some cases, within the same song, on Revolver’s unparallelled music palette.

For the four Beatles, Revolver was the first time they had made an album self-consciously, realising it completely as a whole composed of more than the sum of its parts. It was the album, what they felt like a Beatles album should sound like at the time. It did what an LP is supposed to do. And that’s why it’s “a revolver”, as McCartney puts it.

It’s fitting that the album sits slap-bang in the middle of The Beatles’ discography. The culmination of the development in songcraft, musicianship and tentative studio experimentation that came before it. And the harbinger of further revolutions in music coming from The Beatles.

If I had to recommend one album to someone who’d never heard The Beatles before, it’d be this one. “What’s the album about?” they might be inclined to ask. The answer: just spin it and see.