Don’t look over your shoulder, but AI is coming. Whether its imminent approach is a bad thing remains to be seen. When I recently spoke to Yihao Chen, the man set to (potentially) change music forever with ITOKA, I was positively comforted. ”You already know that The Beatles successfully adopted synthesiser at the very, very beginning, using Yamaha synthesisers in a lot of their famous songs, and it was a hit! Now everybody loves it and admires the way that they adopted new technologies as a sound source in the music,” the soft-spoken, well-mannered, entirely non-villainous Chen explained, satisfying my need for dystopian-free reassurance.

But then, a much more perturbing remark was espoused. ”Those people who are not willing to adapt and not willing to use this technology might suffer from the gap that we create between the people who are using data and who are not using it,” he said. I currently still don’t even have Apple Pay and suffer every time I leave my wallet behind, so this sent a chill. Moreover, it was a remark that highlighted that it was not just my fellow techno-inepts that would suffer, but that the notion of a gap would most likely be driven in favour of the powers that be… as it so often is in the capitalist world.

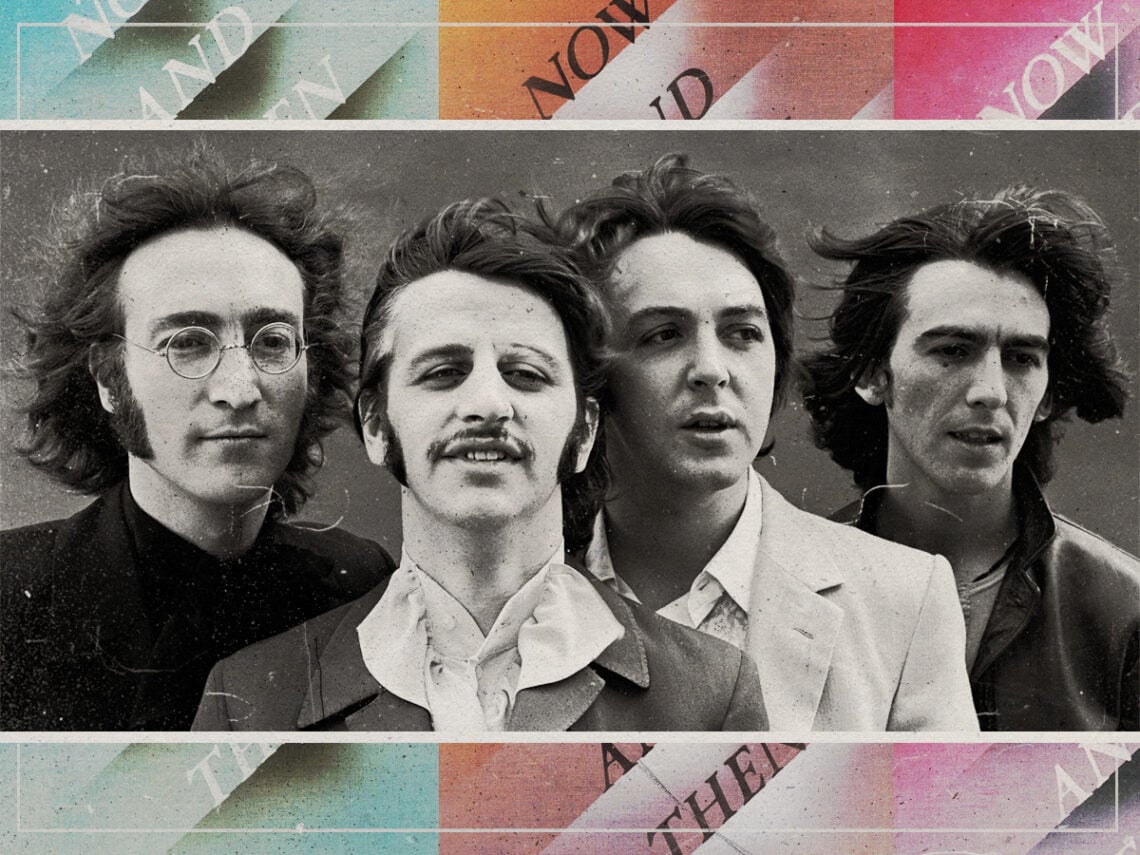

So, when The Beatles released their final song recently, it turned out to be so momentous that Clem Burke told us, “Being here in London on the day of its release, I’m finding it a very poignant and profound listening experience with the string arrangement adding to its emotional impact,“ and millions of others matching that sentiment, it was hard to tell whether such cause for celebration incorporated the fact that suddenly AI seemed like a tool for harmonious progress, or whether the potential pitfalls had been glossed over?

Firstly, I wondered how on earth John Lennon had been brought back from the dead with such verity. “Peter Jackson’s team built an AI machine learning-based technology that could analyse the frequencies of each of the instruments in the old demo recording that John Lennon made,“ Michele Darling, chair of Electronic Production & Design at the Berklee College of Music, explained. “In this case, it could make out the difference between John’s voice and the piano.“

Darling continued: “Machine learning technology could be taught to learn a voice or instrument based on a data set of sounds that it is fed. The technology could learn voice and piano, in hopes of it being able to identify and isolate similar timbres in the old recording.“ In other words, the tech was essentially a sonic gold pan, able to sift through the mix of a muddy recording and separate out the constituent parts. Similar tech has been used in oil refineries for decades as chemical signatures allow for separation.

We can then refine further, and the use of AI for ‘Now and Then’ is seemingly no different. “Separating the voice and instrument tracks can improve quality,“ Darling says. “For instance, the voice and piano were recorded on the same microphone, and when the piano became too loud, we would lose the voice a little bit. It’ll be more clear if the piano is not in the way. Once you have an isolated voice track, you can add more common music production tools and processing to improve the sound of the voice, such as taking out extra noise, increasing the volume, and making it more balanced overall.“

When I ask whether AI fills in any blanks – a factor that would surely blight the process by placing it on a slippery slope that’s simply not cricket – I’m assured that “it’s all John. It’s his voice from the original recording. It’s just been taken from the bad recording with the use of AI machine learning and then enhanced and sweetened with noise reduction tools and other processing that are typical in music production these days.“

With that in mind, AI should really be seen as an advancement of what is already commonplace in music as opposed to some new incumbent force. But will the way it has been deployed for ‘Now and Then’ become a cost-effective effort that heralds a new future for music’s past? “Well, what if you could improve on the quality of an old recording?“ Darling asks. “Wouldn’t you want to hear the sounds more clearly if you could? This particular technology, right now, is being explored. Peter Jackson’s technology isn’t accessible to everyone, but I believe that more of it will become accessible in the near future. Whether it’s Jackson’s technology or others remains to be seen.“ But it won’t stop at ‘Now and Then’; that much is certain.

However, the final Beatles song should be seen as the benchmark. The triumph of the track, the reason it has punk drummers like Clem Burke, my better half, and no doubt millions of others crying, is because AI was subsumed as a mere aid in the fitting farewell of a band who continually used technology to advance artistry. As Ryan Dann, the ambient musician behind the Holland Patent Public Library, told me, “I don’t think that AI is going to replace art because I think the core of art is that you feel like you are connecting with somebody else,” even when they are faceless.

“That there is a person on the other end of the art, and they are trying to communicate something. When you connect with a piece of art, you’re connecting with a person. You’re not just connecting with images, you know what I mean?“ he continued. “When you look at the lilies in a Monet painting, you’re seeing the fact that the guy was going blind, and he’s trying to pull in the very last bits of light he was going to ever have access to and put it in a painting. Even if AI created something similar, you wouldn’t feel anything because, like, who cares?”

So, the vital pivotal remark when it comes to ‘Now and Then‘ is simply, “It’s all John.“